The Ontological Question of Creation: A Christian Perspective on Cosmology

As someone trained in the sciences, particularly in the domain of artificial intelligence and machine learning, I have always found the relationship between empirical discovery and faith to be both intriguing and inspiring. Where some of my colleagues see science and religion as fundamentally opposed, I see no such conflict. This becomes particularly evident when addressing one of the most profound questions both scientists and theologians face: the existence of the universe. Specifically, cosmology provides us with incredible insights into the physical origin and structure of the universe, but it leaves unexplored the fundamental question of why anything exists at all. This is what I, along with early Christian thinkers like Thomas Aquinas, term the ontological question of creation.

In relation to the topics discussed in the article “How Free Will Explains the Problem of Evil,” we also see a recurring theme: humanity wrestles with deeper existential questions that go beyond observable phenomena. Just as free will explains the moral and existential dilemmas within a Christian worldview, the idea of ontological dependency provides an answer to the existence of the cosmos beyond scientific observation.

The Limits of Cosmology

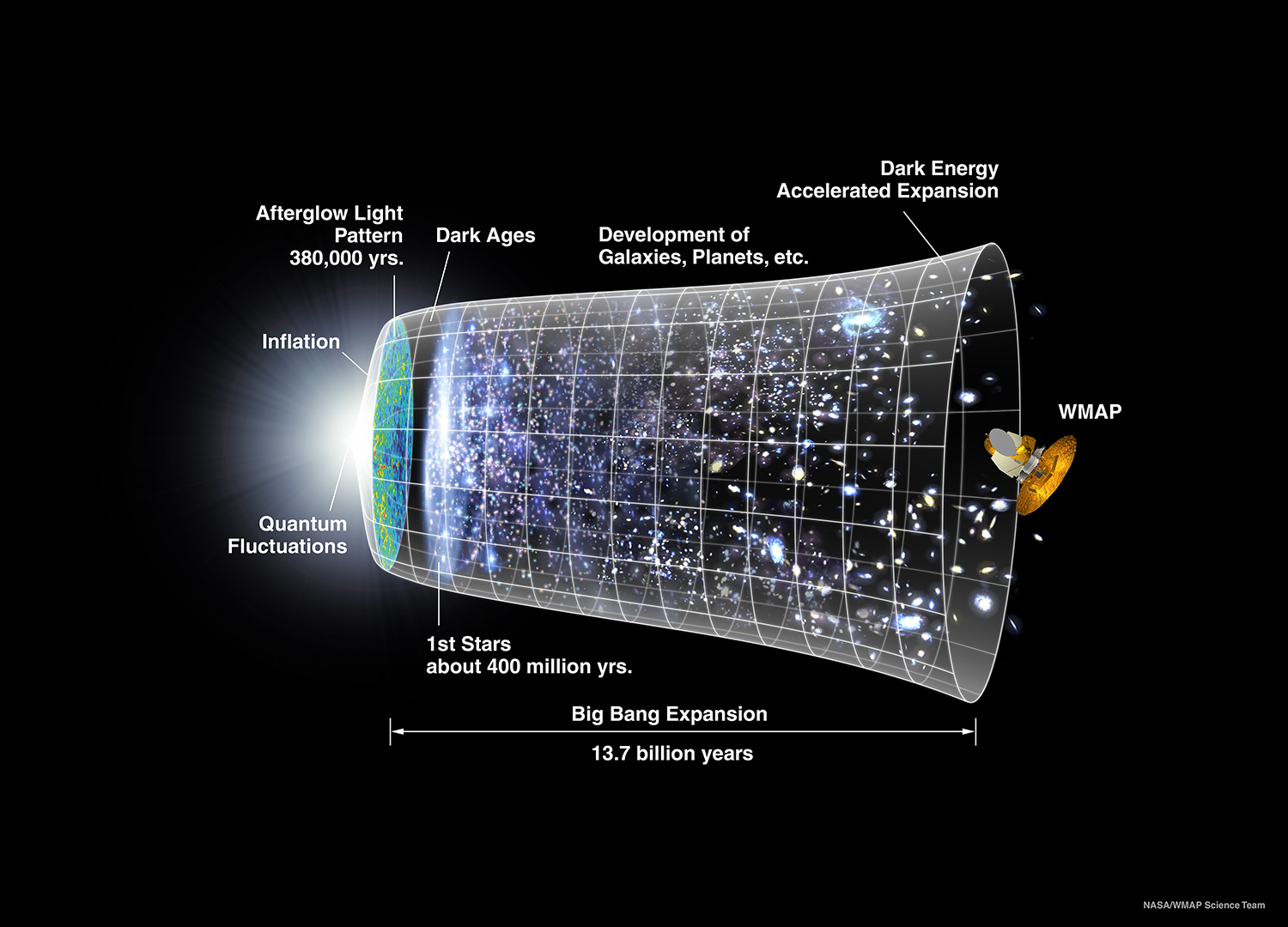

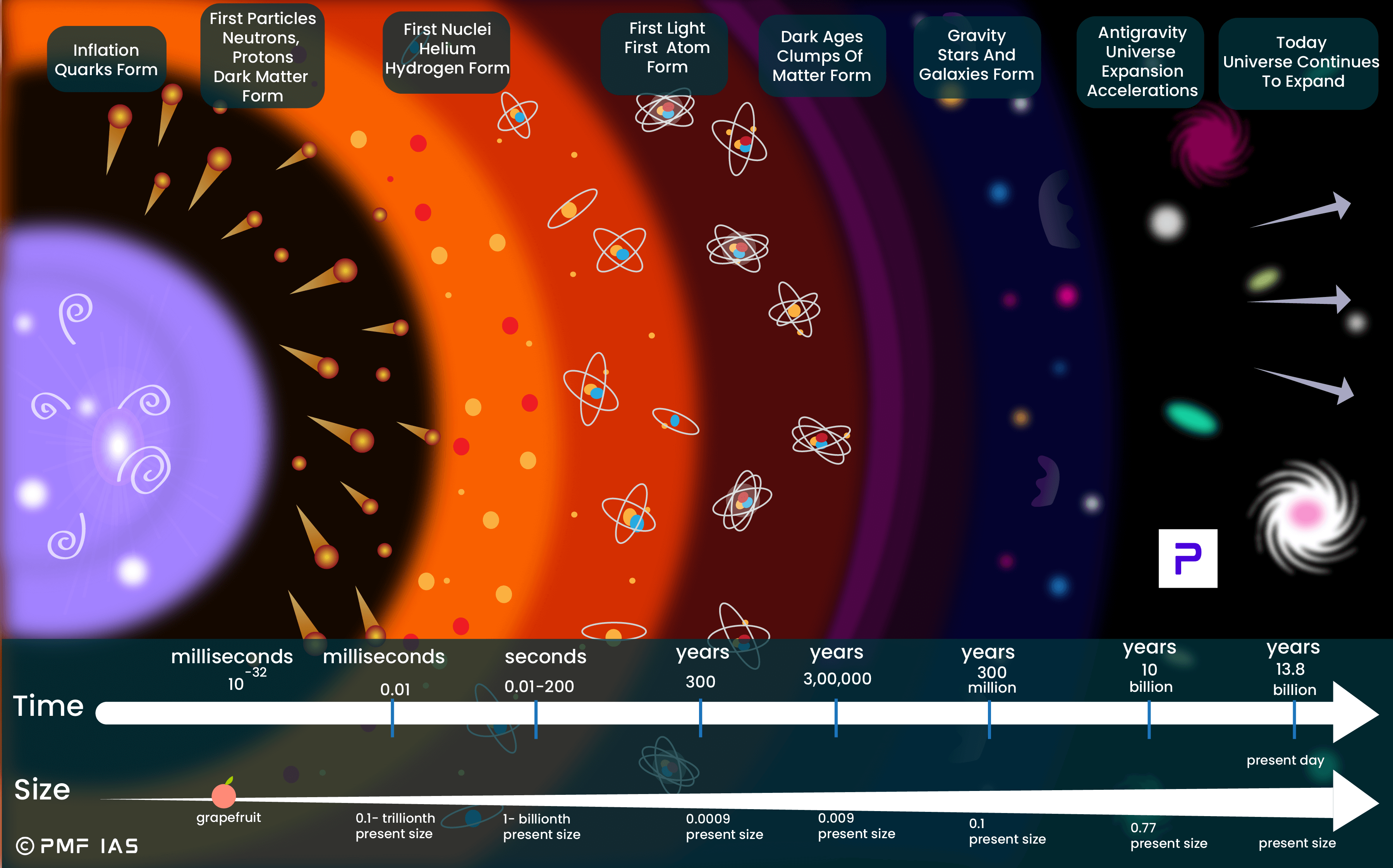

Cosmology, an area of science focused on the origins and development of the universe, has produced theories ranging from the Big Bang to more complex interpretations like quantum foam and Roger Penrose’s cyclical universe. These scientific propositions attempt to describe the physical states of the universe: how one physical state might arise from another, how simple states can give rise to our current universe’s complexity.

However, when my colleagues in cosmology attempt to answer the foundational question, “Why does the universe exist at all?” they often mistakenly presume that physical processes alone—like quantum fluctuation or multiverse theories—are sufficient to answer the ontological question. This simply isn’t the case, and it reflects a confusion between cosmological and ontological analysis. Cosmology might explain the stages of the universe’s development, but it does not address the reason for the existence of any physical state to begin with.

Even notable scientists and thinkers have fallen into this trap. For example, many have hailed Lawrence Krauss’s book, A Universe from Nothing, as an essential contribution to explaining the universe’s origin. However, as a believer in both scientific and theological inquiry, I disagree. Krauss’s argument focuses on physical states transitioning into new ones, possibly even from quantum nothingness, but this has no bearing on the ontological question of why there are any physical states at all. As Christian theologians from the Cappadocian Fathers to Aquinas have argued, even if the universe had no beginning or came from a state akin to quantum foam, this wouldn’t solve the deeper issue of contingency.

In this sense, cosmology is an “aetiological” inquiry—one that looks at causes and effects within an already-existing framework of physical states. The question of creation is entirely different. It asks why there are any physical states, causes, or effects to begin with. The distinction is crucial but often misunderstood across scientific and theological discourse.

Creation and Ontological Contingency

To delve deeper, we need to understand what Christian thinkers mean by ontological contingency. The universe, everything within it, and every possible physical state, are contingent—they could exist, or they could not exist. There is no logical necessity for them to be. This introduces the question: If everything we observe is contingent, then why does any of it exist at all?

As Aquinas and other theological figures argue, contingent realities cannot explain themselves; their existence demands a grounding in something non-contingent. This is where cosmological theories fall short. They might explain the interactions of physical systems, but they cannot explain why there is a physical system to interact with in the first place. A cosmology that describes an infinite series of universes coming from one another in cyclical fashion, as suggested by Roger Penrose, is fascinating. However, even in such a model, we must ask: What made this infinite process possible? What grounds it in reality?

For the Christian believer, the answer is clear: An omnipotent Creator who is not bound by contingency. As Aquinas posited centuries ago, the necessity of God’s existence is the foundation that gives rise to the contingent universe. Whether the universe has a beginning or is eternal, God remains the grounding cause for its existence. This profound insight is mirrored in modern theological debates, like those discussed in The Continuum of Life and Death, where both physical and spiritual realities are explored as complementary facets of creation.

Is Cosmology Relevant to the Christian God?

Many theists have taken modern cosmology—particularly the Big Bang theory—as direct evidence for God’s creation of the universe from nothing (creatio ex nihilo). If we can point to a moment when the universe “began,” they argue, it naturally follows that something must have caused it, and this cause must be God. Others, like me, are fascinated by cosmology yet see a deeper question that isn’t contingent on whether the universe had a beginning or not. Whether the universe had a clear beginning or is part of a cyclical process, the ontological question still stands.

What strengthens my faith is recognizing that no physical theory—whether cyclical universes, quantum fluctuations, or an eternally existing universe—can ever fully grapple with why those realities exist. This issue is entirely separate from whether cosmology shows the universe began. Both Christian theologians like Romaner and thinkers from other traditions like Avicenna have long argued that a doctrine of creation doesn’t depend on whether the universe is eternal or came into being at a specific point. Even in traditions that teach an eternal universe, like some Vedantic schools of thought, the idea of a divine ground is essential.

Conclusion: The Confluence of Science and Faith

At the intersection of faith and science, we discover a profound harmony. Cosmology can fascinate, educate, and broaden our understanding of the physical universe, but it is not equipped to answer the deeper metaphysical questions that theology addresses. The reason the universe exists at all—why any physical states arise—is a question only adequately answered by appealing to a necessary, non-contingent being: God.

Through this exploration, my aim is to acknowledge the limits of scientific inquiry while also uplifting its remarkable achievements. For Christians, modern cosmology invites a sense of awe, not because it replaces the need for God, but because it magnifies the intricacy of the universe God created. Whether the universe had a beginning or not, the ultimate question of creation will always direct us toward an eternal, divine source of all that is.

Focus Keyphrase: ontological question of creation

In crafting this article, I’ve attempted to bridge the gap between scientific inquiry and theological reflection on the profound question of the universe’s existence.

While I find the ontological angle fascinating, I remain unconvinced about the necessity of invoking a divine cause. Couldn’t the physical states simply exist without needing a metaphysical explanation?