The Power of Good Explanation: Uniting Faith, Science, and Human Understanding

Throughout my spiritual and intellectual journey, I’ve often wrestled with the dichotomy of faith and reason. How do these two seemingly disparate worlds—science, with its rigorous need for testable theories, and faith, built on trust and unseen truths—interact? I’ve come to realize that the unifying thread between them is the principle of good explanation.

The concept of “good explanation” is something I’ve found particularly powerful, and it bridges the gap between science and faith more seamlessly than I initially thought possible. Not only does this principle provide clarity in scientific exploration, but it also serves as a guide for how we understand morality, aesthetics, and even spiritual truths.

In previous posts, such as “The Principle of Good Explanation: Bridging Science and Faith for Deeper Understanding”, I explored this concept further, touching on how good explanations not only unify science and faith but also provide us with a versatile tool for navigating moral and philosophical questions in our everyday lives. Today, I’ll continue that discussion by diving deeper into the role of explanation as the common foundation of all fields of human knowledge, including faith and science.

Testability: Foundational, but Not Absolute

One of the core principles of scientific endeavor is testability. This principle asserts that any claim about the physical world must be subject to testing and observation. A theory must make predictions that can be tested against empirical data.

This principle of testability is indeed a hallmark of science. It’s made remarkable breakthroughs possible, from quantum mechanics to biological evolution. Yet, as I reflected on the boundaries of testability, it became clear that not all “truths” fit neatly into this box. The principle of good explanation transcends the limits of testability while simultaneously encompassing it.

Consider, for instance, the realm of aesthetics. Can we test why Mozart’s music is more aesthetically pleasing than the sound of rocks being smashed together? Certainly not in a scientific sense. Yet, we instinctively know Mozart’s symphonies to be more “beautiful” and harmonious than random noise. This is where the principle of good explanation provides clarity—some truths are hard to vary even though they may not be empirically testable.

The Universal Thread of Good Explanation

The principle of good explanation asserts that an explanation is “good” if it cannot easily be modified without losing its ability to account for what it claims. This principle is not exclusive to science, and that’s where its power lies. Good explanations find their application in fields as diverse as morality and aesthetics, areas often assumed to be matters of personal opinion or taste.

In many areas of life outside the physical sciences, we still deal with objective truths, even though we may not yet have the tools to fully analyze them. When we think about a just society or the moral implications of forgiveness—themes I’ve previously reflected on in posts like “Overcoming Challenges with Faith: Trusting God’s Plan Through Adversity”—we are striving for explanations that reflect a harmonious, moral truth as much as physicists seek truths in the natural world.

But how does this good explanation manifest in practical terms as we navigate our faith? Think about the concept of forgiveness. Christianity offers a profound explanation that resonates deeply, as it accounts not just for the person seeking peace but also for the entire relational structure between individuals. It’s an explanation that, if varied, would fail to offer the kind of grace, redemption, and reconciliation central to Christian ethics.

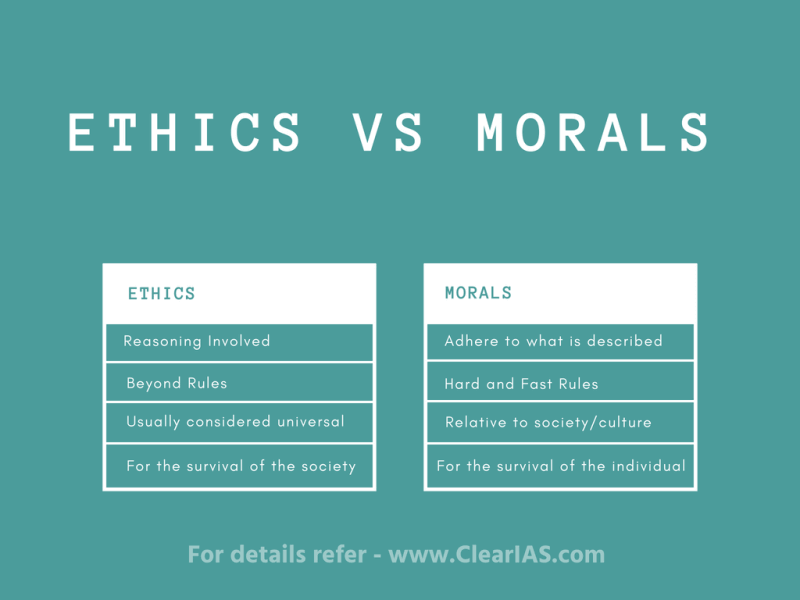

Good Explanation and Morality

So, how does the principle of good explanation apply to morality? I often reflect on how essential this principle is in guiding our ethical decisions. Just as testability cannot entirely account for the truth in music or art, it cannot fully resolve moral questions. Yet, good explanations grounded in Christian ethics tend to be those that are hard to vary while still doing justice to human dignity, community, and compassion.

Consider our responsibility for justice and the alleviation of poverty, a topic I’ve engaged with in depth during my travels and in posts like “Embracing Responsibility Through Faith”. The challenge is not merely understanding why injustice exists—that’s easy enough—but what our Christian obligation is when faced with the suffering of others. The explanation offered by scripture, grounded in love, service, and demonstrating God’s compassion for the marginalized, is incredibly powerful and unmistakable in its moral clarity.

A good explanation of morality must be able to withstand scrutiny and not be easily altered without losing its sense of truth. God’s moral mandates, like the imperative to “love thy neighbor” or to defend the rights of the oppressed, have remained constant through ages of social change because they are fundamentally good explanations of how we can live justly, compassionately, and in alignment with divine will.

The Integration of Faith, Science, and Systems Theory

In some areas of human knowledge, we recognize the overlap between different disciplines—for example, how General Systems Theory attempts to find principles unifying different fields of science. But could this idea go even further, into a unification of all types of human understanding?

The truth is, the science of physics and morality cannot be entirely separated, as the pursuit of truth demands guiding moral principles such as intellectual honesty, integrity, and tolerance. Jacob Bronowski once said appropriately: “The most powerful drive in the ascent of man is his pleasure in his own skill.” Most importantly, these essential moral virtues—the foundation of science—are principles born out of philosophy and, for people of faith like myself, scriptural truths.

| Field | Good Explanation Principle |

|---|---|

| Science | Theories that are testable and predict phenomena |

| Aesthetics | Art that consistently evokes human emotional and intellectual responses |

| Morality | Ethics that promote human flourishing and social harmony |

This realization that the principle of good explanation can be applied across all fields of knowledge is profound. It tells us that our quest for understanding the natural world and our moral responsibilities are interconnected. As we stand on the brink of new advancements, especially with emerging technologies like AI, maintaining a commitment to good explanations in both science and morality will help ensure that our innovations serve the greater good.

Conclusion: Faith and Science, United by Explanation

Ultimately, I find that faith and science are inextricably linked through the principle of good explanation. Both seek truth, though they do so in different realms—the physical and the spiritual. And yet, their goal remains the same: to account for the world we live in and our relationship to it.

As I continue to navigate my life, balancing my professional work with my spiritual calling, I see more and more how these principles can work together harmoniously. Whether in my personal journey of faith or in examining how we can ethically use technology, the principle of good explanation continually refines my understanding of God, the universe, and my role within both.

Let us, as faithful individuals and seekers of truth, strive for good explanations in all things. After all, these explanations not only reveal truths about the world God created but also help us lead lives filled with purpose, joy, and compassion.

Focus Keyphrase: good explanation

This piece really resonated with me. I appreciate how you tackled the complex intersection of faith and science—something I’ve wrestled with myself. The idea that good explanations unify both realms inspires deeper reflection. Thank you for not shying away from asking the hard questions.

It’s fascinating to see how the principle of good explanation isn’t limited to one area of thought but instead weaves faith, science, and ethics together seamlessly.